Lalla Zaynab (1850–1904) was an Algerian mystic of the Rahmani order, and daughter of the shaykh and polymath Muḥammad ibn Abī al-Qāsim. She spent her youth in her father’s zāwiyah, or Sufi monastery, at El Hamel, surrounded by the women of the ḥarīm (being her father’s wives, other daughters, as well as the cloistered disinherited and indigent women with no male gaurdian) as well as insurgents, refugees of revolt and scholars of the time. In 1877 after a heart attack, Ibn Abī al-Qāsim went to Tamsa to have his will composed. He willed to Zaynab a share of property equal to that which a male heir would receive, having had no sons, while his other daughters inherited the usual share for daughters. He died from a heart attack in 1897 while returning to El Hamel from Algiers. By this time, Captain Crochard of the French army at Bou Saada had investigated and put French backing behind Zaynab's cousin Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥajj, claiming to have recieved a letter from Ibn Abī al-Qāsim nominating him. Zaynab had lived with refugees from the Muqrani revolt and so grew to become averse to French governance and colonialism, making her a successor adversarial to French authorities. Although Ibn al-Ḥajj was unpopular for his perceived worldliness, when he came to zāwiyah to assert his inheritance (and Zaynab’s ineligibility), the dispute between his partisans and hers became so heated that it broke out in violence. Zaynab had insisted that her inheritance of her father’s estate extended to inheritance of his leadership and his barakah, or divine blessings and saintly abilities, and that the letter Captain Crochard claimed to have received was a forgery. Ibn al-Ḥajj threatened to lock Zaynab in the ḥarīm. In retaliation She barred Ibn al-Ḥajj and his supporters from the zāwiyah.

The struggle to assert her claim to inheritance would continue for the remaining years of Lalla Zaynab’s life. Ibn al-Ḥajj established a rival zāwiyah, although he would only garner thirty adherents. Supposedly, once when the two quarrelled publicly, the earth shook, and her father’s voice was heard declaring Zaynab to be his heiress, and that she inherited his barakah. This alleged incident solidified her saintly authority in her followers’ consciences, though some would follow her cousin, and others still believed the zāwiyah should rescind to a descendant of an ancestor of Ibn Abī al-Qāsim. Zaynab further decided to pursue legal action against her cousin and the army at Bou Saada. She made her motion under the legal advocacy of the Martinique lawyer Maurice l’Admiral, and the case resulted in the Algiers administration ordering the French army to cease their interferance in her affairs. With Ibn al-Ḥajj spiritually and legally neutralized for the time being, Zaynab would later relent on her moratorium against him, allowing him back to the zāwiyah. She would have to continue to assert that authority though, as the army at Bou Saada would not yet relent against her. In 1899, after having the zāwiyah rebuilt the year prior, she would have to repulse accusations from a Sa‘īd ibn Lakhḍar that the zāwiyah owed him two million francs. Ibn Lakhḍar even compelled Ibn Abī al-Qāsim’s widows to leave their ḥarīm and travel from El Hamel to Algiers to give their oaths that they were unaware of money owed to him. Zaynab summarily refuted the accusations, and, against Captain Crochard’s expectations, she maintained her father’s fortune and estate.

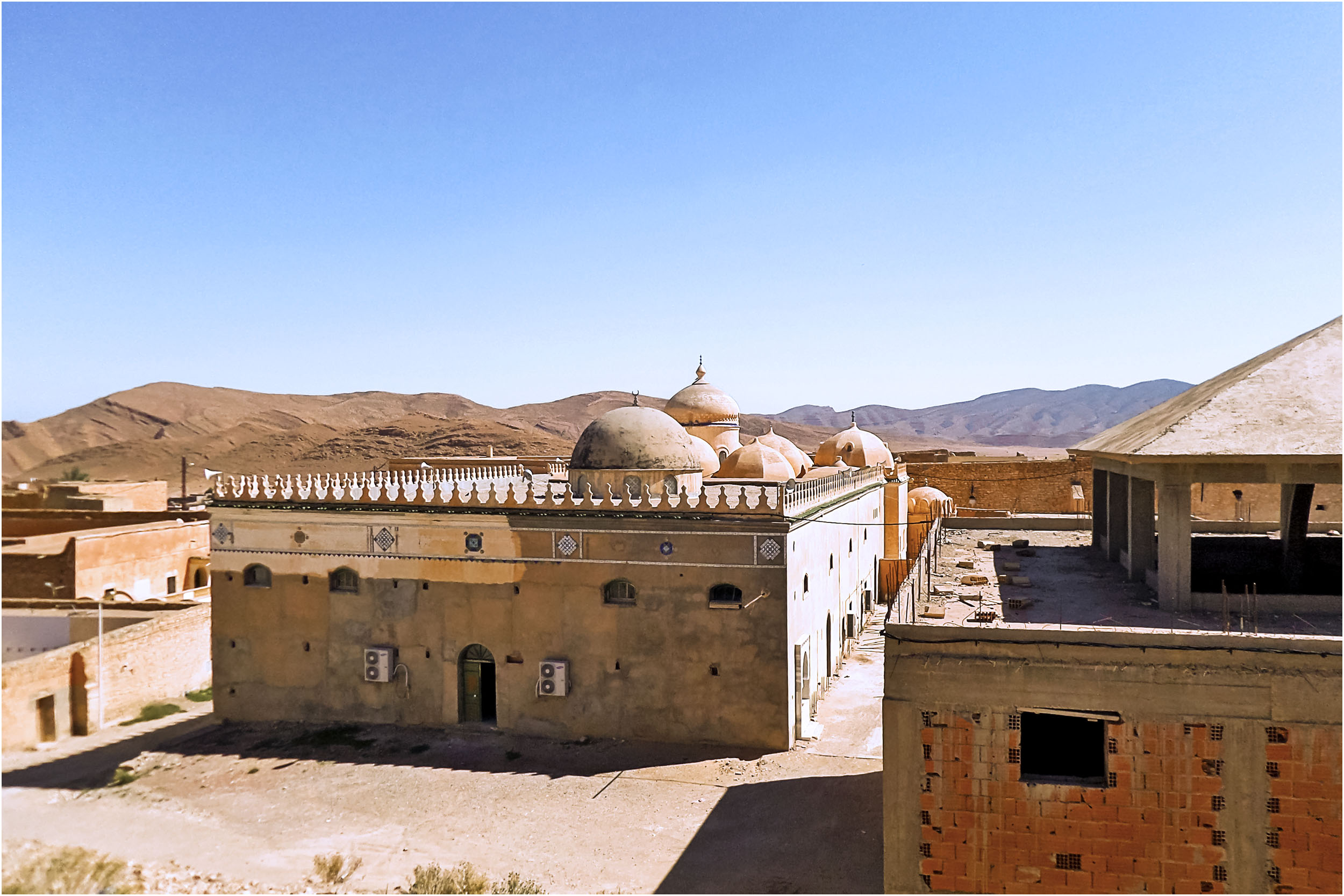

Zaynab had declared celibacy early in life (a declaration she would reinforce when Ibn al-Ḥajj proposed marriage to split the inheritance), and this afforded her a great deal of social mobility. On account of her celibacy, she left her face uncovered. She was said to have resembled her father a great deal, and she was described as wearing the white garb of Bou Saada women and having a face with small tattoos, as was the fashion for North African women. She also travelled often, meeting with religious and worldly powers, drawing crowds of devotees where she went. She even befriended the mystic Si Mahmoud Saadi, despite their deep eccentricities standing in contrast to her personal austerities. Her travels and contest for authority would end, however, in 1904, when she died of respiratory failure. The zāwiyah would finally pass to her cousin, after which it would fall into financial straits and come into French dependence and decline. The zāwiyah remained an eminent institution though, and with Zaynab buried beside her father, it is still a place of pilgrimage, although, unlike her father and ensuing Rahmani shaykhs, her portrait is not displayed.

I: “Lalla Zineb ,Une femme avec un sacré caractère.” Ethnopolis, 11 May 2015, ethnopolis-net.over-blog.com/2015/05/lalla-zineb-l-insoumise.html.

II: Kaki, Habib. “El Hamel - Zaouia زاوية الهامل - panoramio (4).” Wikimedia Commons, 2 Oct 2015, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Hamel_-_Zaouia_%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%84_-_panoramio_(4).jpg.

Clancy-Smith, Julia A. “The Shaykh and His Daughter: Implicit Pacts and Cultural Survivor, c. 1827–1904.” Rebel and Saint: Muslim Notables, Populists Protest, Colonial Encounters (Algeria and Tunisia, 1800–1904). University of California Press, 1994, pp. 214–253, UC Press E-Books Collection, 1982-2004.

El Hassani, Mohamed Kacimi. “Lalla Zineb, l’insoumise [Lalla Zayna, the Rebel].” El Watan, 20 April 2013, www.elwatan.com/archives/arts-et-lettres-archives/lalla-zineb-linsoumise-20-04-2013.

Lalla Zineb • Lalla Zeyneb • Mohammed Belqacem • Mohammed Belkacem

North Asia • Rahmani Order • Sufi • Spiritual Master • Mystic.